On this date in 1922, 14-year-old Leonard Thompson became the first person to receive an insulin injection as a treatment for diabetes, transforming the once-fatal disease into a manageable condition and saving countless lives worldwide.

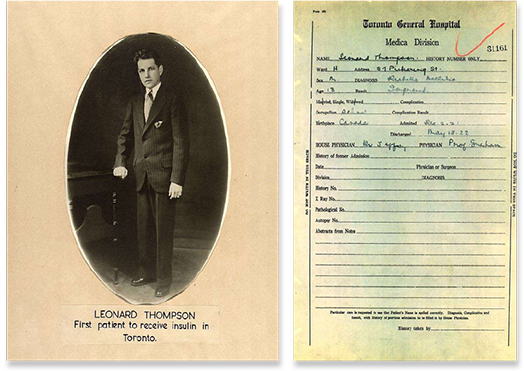

On January 11, 1922, a 14-year-old boy named Leonard Thompson became the first person in history to receive an insulin injection as a treatment for diabetes. Born in 1908 in Toronto, Canada, Leonard had been diagnosed with diabetes at age eleven and was put on a strict diet that could only manage his symptoms temporarily. By the time he reached the hospital at fourteen, he weighed just 65 pounds, was much smaller and weaker than a boy his age should be, and was drifting in and out of consciousness. Desperate to save their son, his parents Harry and Florence agreed to let Leonard test a revolutionary new treatment.

Source: NobelPrize.org

Thompson's first insulin dose on January 11 had an apparent impurity that caused an allergic reaction. Researchers quickly refined the extraction process to improve the cow pancreas insulin, and his second dosage was successfully injected twelve days later, on January 23. The results were remarkable. According to his medical records, "The boy became brighter, more active, looked better and said he felt stronger." Within a few months, Leonard had recovered enough to return home. For the first time in history, diabetes was no longer a death sentence. As Professor Juleen Zierath of the Karolinska Institutet described it: "It was a miracle."

Source: UMass Medical School

The breakthrough came at the University of Toronto in the summer of 1921, when surgeon Frederick Banting and research assistant Charles Best successfully isolated insulin from canine test subjects. Banting had reportedly woken up in the middle of the night with a hypothesis, scribbling it down on a piece of paper dated October 31, 1920. His key insight was that another substance in the pancreas, trypsin, was breaking down insulin before it could be extracted. Working in John Macleod's laboratory, Banting and Best treated dogs so they no longer produced trypsin, allowing insulin to be extracted successfully. Their discovery was announced to the world on November 14, 1921.

Source: NobelPrize.org

When Banting and Best first isolated insulin from dogs, colleagues remarked that it looked like "thick brown muck." Biochemist James Collip joined the team to purify the substance so it would be safe for human use. Together, they refined the extraction process from cattle pancreases obtained from slaughterhouses, creating a formula pure enough to save Leonard Thompson's life. Banting, Collip, and Best were awarded U.S. patents on insulin and the production method, but sold them to the University of Toronto for $1 each. As Banting declared: "Insulin does not belong to me, it belongs to the world."

Source: NobelPrize.org

News of Leonard's remarkable recovery spread quickly, and demand for insulin surged. "One by one the implacable enemies of man, the diseases which seek his destruction, are overcome by science. Diabetes, one of the most dreaded, is the latest to succumb," reported The New York Times. The researchers refined their production techniques to manufacture insulin in larger quantities, and in October 1923, the first commercial supply was shipped. By 1923, insulin had become widely available worldwide, saving countless lives.

Source: UMass Medical School

In October 1923, just 21 months after Leonard Thompson's first injection, Banting and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. To this day, it remains the shortest period of time that a Nobel Prize was awarded following a medical breakthrough. However, the laureates were unhappy that their collaborators' contributions had not been recognized, so they shared the prize money with Best and Collip. The discovery sparked decades of further research, with additional Nobel Prizes awarded to scientists who advanced understanding of insulin's structure and function, including Frederick Sanger (1958), Dorothy Hodgkin (1964), and Rosalyn Yalow (1977).

Source: UMass Medical School and NobelPrize.org

Leonard Thompson lived for 13 years on insulin and died on April 20, 1935, at the age of 27. While his life was far longer than it would have been without insulin, his legacy extends far beyond his own survival. More than 100 years after its discovery, insulin continues to be used to help over 400 million people worldwide with diabetes. The revolutionary discovery paved the way for synthetic insulin, ultra-rapid and ultra-long-acting insulins, and ongoing research toward potential cures. Today, people with Type 1 diabetes who have access to insulin can have a life expectancy approaching that of non-diabetics.

Source: NobelPrize.org

January 11, 1922, stands as one of the most important dates in medical history. What began as a desperate attempt to save a dying teenager became a watershed moment that transformed diabetes from a fatal diagnosis into a manageable condition. The discovery of insulin represents one of medicine's greatest triumphs and continues to inspire hope that future breakthroughs will one day eliminate diabetes entirely. As Professor Juleen Zierath of the Karolinska Institutet says today: "I'm really hopeful that researchers will come closer to finding a cure for diabetes and I believe that we have great tools in our hands."